The Dos and Don’ts of Design Charrettes

What Is a Design Charrette and Why Does It Matter?

A design charrette is an intensive, collaborative workshop used in architecture and engineering to explore ideas, surface challenges, and align teams around a shared vision. Common in architecture charrettes and large-scale planning efforts, charrettes bring together designers, engineers, clients, and stakeholders to solve problems in real time. This post defines design charrettes, outlines proven charrette protocol, and shares practical guidance on how to run a design charrette that leads to clarity, alignment, and faster decision-making.

Design charrettes aren’t what they used to be – and for good reason.

The concept originated centuries ago in France, where architecture professors would send a cart (or charrette) around to collect student work. If students weren’t finished, they would jump into the cart or run alongside it, continuing to refine their designs until it was time to present. That history gives us the modern charrette meaning in architecture: focused, time-bound collaboration under real constraints.

Today, design charrettes may resemble structured brainstorms, where architects, engineers, contractors, and clients work side by side to shape big ideas. Modern charrettes are collaborative and problem-seeking, pushing creative boundaries while keeping client leaders engaged—and prepared to defend what comes out of the studio.

If you’re planning a design charrette for your next project, the following guidelines can help set it up for success.

How Do You Start a Design Charrette Without Predetermining the Outcome?

Successful design charrettes begin with clear goals and a plan—not a fixed solution. A charrette only works when participants are free to explore ideas without hidden agendas or predetermined destinations.

If you are forming a charrette with a preconceived idea in mind, don’t bother. Instead, when planning a charrette with your team and client:

- Define goals that are obtainable and yet demanding, so that expectations can be managed.

- Build out a schedule that factors in breaks and keeps a demanding pace.

- Try to find a location on the project site, which will get everyone off their home turf.

- Strive for diversity in authority, culture, gender and expertise, and know the personalities and group dynamics before you meet if possible.

Establishing this foundation is a critical first step in learning how to run a design charrette effectively.

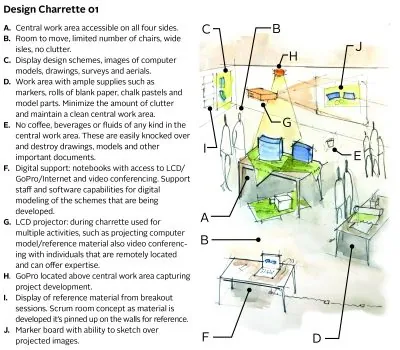

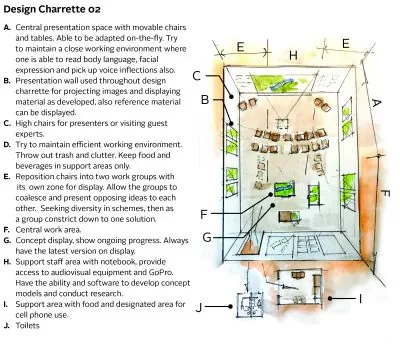

How Do You Create the Right Environment for a Productive Design Charrette?

A productive design charrette depends on consistent participation, shared focus, and disciplined facilitation. The facilitator’s role is to amplify ideas while guiding the group toward a coherent outcome.

Once the charrette is scheduled, it should be treated as one of the most important moments in the project lifecycle. To support meaningful collaboration:

- Clarify each participant’s expertise and expected contribution.

- Maintain one primary conversation to avoid fragmented discussions.

- Set clear rules for phone use and provide space outside the room for calls.

- Study project materials thoroughly so the conversation stays informed and efficient.

- Use a “parking lot” board to capture ideas that may be valuable later.

- Develop content in native tools (SketchUp, Excel, Revit) so ideas can evolve in real time.

These principles form the backbone of effective charrette protocol.

How Can Technology Support Virtual Design Charrettes?

Virtual design charrettes can be just as effective as in-person sessions when structured intentionally. The right roles, tools, and facilitation ensure collaboration remains dynamic and visual.

In distributed or remote environments, virtual charrettes help maintain project momentum. Best practices include:

- Assigning three clear roles: a subject matter expert, a moderator, and a software lead.

- Using overhead or document cameras to share sketches and markups live.

- Leveraging modeling tools like SketchUp that integrate with video conferencing platforms.

When done well, virtual sessions expand access and flexibility without sacrificing creativity.

Why Is Letting Go Essential to a Successful Design Charrette?

True innovation in a design charrette requires time, discipline, and a willingness to push past initial ideas. The most valuable insights often emerge after the obvious solutions are exhausted.

Creativity is not a single moment; it’s a process. As a charrette progresses, early ideas give way to deeper thinking. To reach that level:

- Surface and resolve underlying concerns during the session, not afterward via email.

- Benchmark competitors and challenge the team to do better.

- Keep the team, goals, and vision intact throughout the process.

- Continue refining ideas after the client leaves, allowing the concept to mature.

- Present the refined vision back to the full group the following day.

Once the group aligns around a shared idea—supported by visuals and rationale—approval becomes faster and advocacy stronger. Everyone involved can explain and defend the outcome.

This shared ownership is often the greatest result of any architecture charrette.

Frequently Asked Questions About Design Charrettes

What is a design charrette?

A design charrette is a focused, collaborative workshop where project stakeholders work together to explore ideas, identify challenges, and align on a design direction. It is commonly used in architecture, engineering, and planning to accelerate decision-making and build consensus.

How long does a design charrette typically last?

Design charrettes can last anywhere from a few hours to several days, depending on project complexity. Many successful charrettes span one to three days, allowing time for exploration, refinement, and presentation.

Who should participate in a design charrette?

Participants typically include architects, engineers, consultants, clients, decision-makers, and sometimes community stakeholders. The most effective charrettes bring together diverse perspectives with clear roles and expectations.

What are common pitfalls to avoid in a design charrette?

Common pitfalls include entering with a predetermined solution, allowing side conversations to dominate, failing to prepare materials in advance, and changing goals mid-session. Avoiding these issues is essential to maintaining momentum and trust.

This article was originally published on March 13, 2018. It was updated on April 11, 2023 and February 16, 2026.